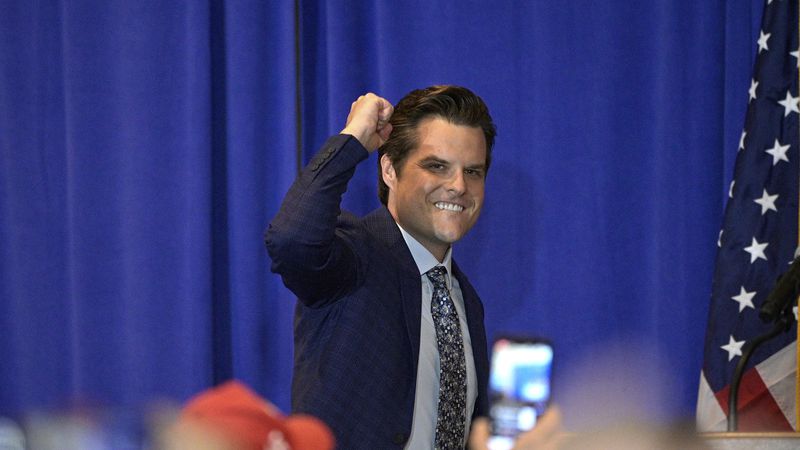

Matt Gaetz helped set off Florida’s marijuana ‘green rush.’ Some of his friends, allies scored big

11 min read

ORLANDO — Less than 24 hours before the Florida Legislature passed the state’s first medical marijuana law in May 2014, Matt Gaetz and other members of the state House of Representatives rewrote the bill to limit who would be able to get in on the ground floor of what has since become a billion-dollar business.

A number of Gaetz’s friends and allies managed to squeeze through that narrow door. Among them:

— The brother of Gaetz’s friend and fellow state Rep. Halsey Beshears, who co-founded one of Florida’s first licensed marijuana companies and amassed a fortune currently valued at about $600 million — and became a major Republican Party donor.

— A Panhandle developer and client of Gaetz’s law firm who invested in another of the state’s first marijuana licensees and who, according to financial and court records, roughly tripled his money in two years.

— Ballard Partners, a prominent Tallahassee lobbying firm, which until recently employed former state Rep. Chris Dorworth, whom Gaetz once described as his legislative “mentor.” The firm was given investment interests in at least three companies that eventually won marijuana licenses, and is now earning $160,000 a year in lobbying fees from a fourth.

— Another of Gaetz’s friends, Orlando hand doctor Jason Pirozzolo, who helped craft that 2014 legislation and then started several marijuana businesses, including a consulting firm that worked with companies applying for marijuana licenses and a professional association that sells sponsorships to marijuana vendors.

Gaetz also worked with some of these same friends in other arenas. In 2019, for instance, Gaetz, Beshears, Dorworth and Pirozzolo were all involved in efforts to replace key leaders at the agency that runs Orlando International Airport, an obscure-but-important entity that spends hundreds of millions of dollars a year on contractors and vendors.

All four have also recently been rocked by a federal investigation that emerged from a probe into disgraced former Seminole County Tax Collector Joel Greenberg.

Gaetz, who is now a member of Congress, is under investigation for potential sex trafficking violations linked to a September 2018 trip to the Bahamas with several young women and with Beshears and Pirozzolo, according to reports by CBS News and Politico.

Investigators have also learned of a conversation between Dorworth and Gaetz about recruiting a third-party candidate to help their friend Jason Brodeur win a state Senate election last fall, according to The New York Times. A similar alleged scheme in a South Florida race has led to charges against a former state lawmaker.

The sprawling federal investigation that emerged from the Greenberg probe has also now expanded to examine whether Gaetz took gifts in exchange for political favors tied to medical marijuana policy, according to recent reports by CNN and The Associated Press.

In a written statement, a spokesperson for Gaetz called him “Florida’s leading medical marijuana policy expert” and said there is “virtually no major player in the industry” with whom Gaetz has not worked in some way.

“While drafting Florida’s initial medical marijuana law in 2014 with State Senator Rob Bradley, Gaetz had no knowledge that any of the people named in your story would seek to enter the industry,” Gaetz spokesperson Harlan Hill said.

“Congressman Gaetz has never accepted a gift or any other thing of value in exchange for his work on marijuana policy,” Hill added. “Congressman Gaetz’s support for marijuana reform is rooted solely in his support for the Americans whose lives can be made better, healthier and easier through the use of marijuana. He looks forward to continuing this work in Congress.”

Neither Beshears nor his attorney responded to requests for comment. Dorworth declined to comment. Pirozzolo declined to comment through an attorney.

None of those four has been charged with any crimes. Greenberg faces a slew of federal charges, including stalking, identity theft, bribery of a public official, wire fraud and sex trafficking of a child.

To be sure, there are scores of entrepreneurs, investors and others across Florida who have benefited, financially or professionally, from the creation and rapid growth of the medical marijuana industry, from a co-owner of the PDQ fried chicken chain to a Russian American billionaire.

The state’s highest-ranking Democrat and a likely 2022 candidate for governor, Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried, was one of Florida’s earliest medical marijuana lobbyists. And famed Orlando trial lawyer John Morgan, who financed a 2016 constitutional amendment that expanded medical marijuana, is now a lender to the state’s No. 2 marijuana company and says he is “inundated on a daily basis with new opportunities.”

“The reality is every single entity that applied for one of the… licenses back in 2015 had some political connections,” said John Lockwood, a Tallahassee attorney who represents a number of marijuana companies. “They lawyered up, they lobbied up, they had various influential people sitting on the board. Everybody was doing everything they could to come up with an application that would hopefully be a winner.”

Gaetz sparked ‘green rush’

Few people did more to legalize medical marijuana in Florida than Gaetz, who personally sponsored the House version of the 2014 legislation that became the state’s first marijuana law and who Morgan once called “the father of marijuana in Florida.”

That initial law only authorized a non-euphoric, low-THC version of the drug. But it nonetheless set off what some called a “green rush” of entrepreneurs, investors and others who were confident the law would expand over time.

That same law, though, strictly limited who could get in on that rush.

That’s because the day before the Florida Legislature formally approved the bill, Gaetz and the rest of the state House rewrote it in a way that severely restricted which businesses could apply to become one of five marijuana “dispensing organizations,” which would then be responsible for everything from growing the marijuana to processing, transporting and selling it.

As a result of the change, the only companies that could apply for dispensing licenses were state-licensed nurseries — and even then, only nurseries that had been around for at least 30 years and had at least 400,000 plants.

Former state Rep. Matt Caldwell, a Republican who is now the property appraiser in Lee County, sponsored the amendment. He said he and Gaetz were the main authors.

Caldwell said the goal was to give control of Florida’s new cannabis business to an industry that hadn’t been actively lobbying for legalization and to ensure that licenses went to well-established, Florida-based nurseries that could manage large operations and avoid conflicting with federal restrictions on interstate commerce.

“There would be no question of a fly-by-night operation wandering into the state and selling smoke and mirrors,” Caldwell said.

In his written statement, Gaetz spokesperson Harlan Hill said Gaetz supported the amendment in part because opposing it would have put the entire legislation at risk, as “many GOP legislators” were wary of medical marijuana.

One of the nurseries that met the criteria was Simpson Nurseries, which is based near Tallahassee and owned by the family of then-state Rep. Halsey Beshears, R-Tallahassee, who voted for the 2014 legislation. Beshears, a former president of the state nursery association, worked for his family’s nursery until 2013, according to his financial disclosures.

Caldwell said he didn’t recall discussing the amendment with Beshears “to any greater extent” than he did with any other House members. And Beshears’ family said at the time they weren’t even sure they would get into the marijuana business.

“We’re certainly not thinking about it today,’’ Fred Beshears, Halsey Beshears’ father, told the Miami Herald and the Tampa Bay Times in a May 2014 report. “I’m very leery about that and anything to do with marijuana.’’

Early movers bank big

Within a year, though, Simpson Nurseries had teamed up with two other large North Florida nurseries to apply for a marijuana license as a company that would later be named “Trulieve.” The leadership team included Halsey Beshears’ brother Thad Beshears and Kim Rivers, an attorney and developer whose husband is a longtime friend of Halsey Beshears.

When Trulieve applied for its marijuana license, the company noted that it had already signed a letter of intent to lease a building in Tallahassee for a retail dispensary. Leon County property records show that property had been purchased by a business led by Kim Rivers in February 2014 — about three months before the Legislature passed that first marijuana law.

Steve Vancore, a spokesperson for Trulieve, said the property was originally purchased as an investment for an office project “that had nothing to do with marijuana.”

“In 2015, what was to become Trulieve needed a space to set up shop, so it made sense to use the office space … on our application,” Vancore said.

Trulieve eventually won one of the state’s first five marijuana licenses, for the northwest region of Florida, after an opaque and subjective scoring process by the Florida Department of Health that a Florida judge would describe years later as a “dumpster fire.”

Today, the now-publicly traded company is by far the largest medical marijuana company in Florida, with 81 stores and more than $500 million in sales last year — more than double its nearest competitor. It ended up using a different location in Tallahassee for its first dispensary.

Kim Rivers and Thad Beshears are two of the company’s largest shareholders. Their stakes are valued at around $800 million and $600 million, respectively, based on their holdings as of March 15 and Trulieve’s current stock price.

Thad Beshears, who could not be reached for comment, has also become a major national Republican Party donor, giving $50,000 in one day during the 2016 presidential election to committees supporting Donald Trump’s campaign and the Republican National Committee. During the 2020 campaign, he donated more than $200,000 to the Trump and Republican committees.

Another early medical marijuana mover was Surterra, which was co-founded in 2014 by entrepreneur Jake Bergmann, who is now the fiancée of Fried, the state’s Democratic agriculture commissioner. Surterra is now known as Parallel, and Morgan, the trial attorney, is one of its lenders. Surterra won the original license for southwest Florida.

The nursery that won the license for northeast Florida was Gainesville-based Chestnut Hill Tree Farm, which at the time had about 406,000 plants, according to its application — just barely clearing one of the thresholds set by the Legislature.

One of Chestnut Hill’s primary investors was Jay Odom, a Panhandle developer and Republican donor whom Gaetz, an attorney, had personally represented before Gaetz was elected to the Florida Legislature in 2010.

Securities and litigation records show that Odom provided about $3.5 million worth of loans to Chestnut Hill, which were later converted into an equity stake of around 27% in the company.

Two years after it won its license, Chestnut Hill and its license were sold to a Canadian company for $40 million cash, suggesting that Odom’s stake would have been worth around $10.8 million. Odom did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Odom continued to use Gaetz’s law firm, Fort Walton Beach-based Keefe, Anchors & Gordon, in lawsuits through that period, including representing his interests in Chestnut Hill. Gaetz left the firm in 2016, the year he was elected to Congress, according to his financial disclosures.

Larry Keefe, Gaetz’s partner at Keefe, Anchors & Gordon who served as the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Florida under President Donald Trump, declined to comment.

Lobbyists join the rush

Most of Florida’s top lobbying firms got in on the early “green rush.” For instance, records show that Costa Farms, the largest nursery in Florida and the winner of the initial license for southeast Florida, spent more than $156,000 on Tallahassee lobbying just in the first six months after the 2014 marijuana legislation became law.

One of the most proactive firms in that initial rush was Ballard Partners, the firm led by Republican Party fundraiser Brian Ballard, whose partners included Dorworth, the former lawmaker and Gaetz mentor, until Dorworth resigned last month.

Records show Ballard signed up at least five nurseries that applied for marijuana licenses.

Three of them, according to application records, awarded the lobbying firm investment interests in their planned cannabis businesses. None of those three firms won any of the first five licenses, though all did so later when the number of licenses expanded as a result of court orders and legislation.

Ballard declined to say what became of those investment interests.

The other two firms that Ballard Partners signed up — Hackney Nursery and May Nursery — were the two North Florida farms that teamed up with the Beshears family’s Simpson Nursery to form the company that became Trulieve.

Lobbying records show that Ballard represented the two nurseries for about a year during the licensing process without reporting any compensation. Ballard declined to say whether he represented them for free, though a spokesperson for Trulieve said neither he nor his lobbying firm was ever given an equity stake in the company.

The work eventually paid off in other ways after Trulieve’s business took off. Today, Trulieve is paying Ballard Partners $160,000 a year to be its lobbyist in Washington, D.C., according to congressional lobbying records.

It wasn’t just big nurseries and plugged-in lobbyists who joined the green rush.

For instance, Jason Pirozzolo, the Orlando hand doctor who has befriended a number of state leaders over the years, started a consulting firm providing medical directors to nurseries seeking marijuana licenses. Applicants were required to hire medical directors as a result of another late amendment to the original 2014 law that Pirozzolo had proposed.

In Jason’s Pirozzolo application to join the board of the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority in 2019, two of the men currently embroiled in scandal with him were among his references: U.S. Rep. Matt Gaetz and former state lawmaker Halsey Beshears.

In Jason’s Pirozzolo application to join the board of the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority in 2019, two of the men currently embroiled in scandal with him were among his references: U.S. Rep. Matt Gaetz and former state lawmaker Halsey Beshears.

Pirozzolo’s business, Florida Health Privilege, provided medical directors to three nurseries that applied for licenses, including Winter Garden-based Knox Nursery, which won the initial license for Central Florida. Pirozzolo and a partner at some point received an equity stake in Knox’s marijuana business, which was valued in 2018 at $2.1 million.

A few years later, Pirozzolo started the American Medical Marijuana Physicians Association, which provided continuing education programs for doctors and organized events promoting the cannabis industry and selling sponsorships to marijuana companies.

Sometimes those sponsors were looking for help from people Pirozzolo knew in Tallahassee.

How medical marijuana, powerful allies fueled rise of Orlando doctor now embroiled in Matt Gaetz sex scandal

For instance, in September 2017, Pirozzolo’s physicians’ association endorsed a medical-records software system developed by a cannabis tech company called Alternate Health Co. The same day, the company hired Brian Ballard and Chris Dorworth to represent it in Tallahassee.

Alternate Health then became a “platinum sponsor” of AMMPA’s annual conference that year. One of its consultants joined the AMMPA board of directors. And the company paid Ballard Partners at least $80,000 over the next year, according to lobbying compensation records.

The Florida Department of Health ultimately approved the company’s software system for use by marijuana dispensaries, according to a company press release.

Representatives for Alternate Health did not respond to requests for comment.

Dr. Richard Tempel, an Orlando doctor who served as the medical director for one of Florida’s early marijuana licensees and has worked with AMMPA over the years, said he hoped the current cloud of controversy won’t do lasting harm to the industry’s prospects.

“I just hope this craziness does not result in consequences for the medical marijuana industry in Florida,” Tempel said. “For while it’s far from perfect, it is helping thousands of people.”

By Jason Garcia, Orlando Sentinel. Martin E. Comas contributed to this report.

Protected by Patchstack

Protected by Patchstack