Up In Smoke | East Bay Express

11 min read

Cannabis regulation could be blindsided by its most difficult health questions

Romanticizing cannabis culture and reliance on outdated findings based on studies of low potency marijuana conducted more than 20 years ago are the two gravest dangers facing the industry in 2021. Medical and recreational users of cannabis are left to swing in today’s Wild West buyer-beware arena, according to two Bay Area medical health experts.

As 16 states and the district of Washington, D.C. have now legalized the recreational use of cannabis and data shows growing belief in claims (backed by science or not) of beneficial outcomes when cannabis is used to treat a wide range of medical conditions, new studies expand. Included in the scaled-up scope is research related to agriculture (specifically, land and water use), legislative action (labor practices, public policy and regulation), business and the economy (tax revenue, banking, underground black markets, big industry investors and more), and cannabis culture (mythology, history and contemporary society’s response to increased accessibility, safety, risk, potency, edibles, topicals, THC, CBD, digital delivery of addiction therapy and other topics). Underpinning it all is medical science research and findings involving the mental and physical health implications of cannabis use. Online, efficacy topics proliferate into cannabis to treat pain, glaucoma, depression, nausea, muscle spasms, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, opioid dependency, and more.

Choosing for purposes of this article to focus on medical cannabis and the latest research and findings, we turned to Dr. Salomeh Keyhani, MD., a general internist and health services researcher in the Department of General Internal Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and Keith Humphreys, a Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford University, and an affiliated faculty member at Stanford Law School and the Stanford Neurosciences Institute.

Keyhani is currently leading multiple studies involving, among other topics, the cardiovascular and/or pulmonary health effects of marijuana use; tobacco and cannabis use and the impact on lung function, the association of marijuana use with cancer, and public perceptions as formed by traditional and social media and how those platform cover the scientific evidence associated with the potential benefits and harms of cannabis use.

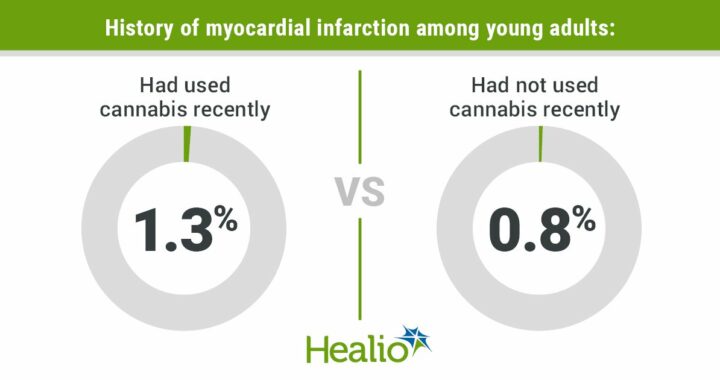

Beginning our discussion with the effect of cannabis on heart disease, lung function and falls and hospitalizations when used by elderly adults, Keyhani says, “Science has preliminary findings, but I am hesitant to make absolute statements.” She says speaking prematurely about findings is “not prudent” and offers a well-known quote: “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” (The words have been attributed to cosmologist Martin Rees and astronomer Carl Sagan, among others.) Under those caveats, Keyhani provides valuable information for consumers and the general public.

“I hear people saying cannabis is safer than tobacco and alcohol—although it’s illegal, unlike those substances—and it’s really not a scientific statement. It’s more of a public policy question. We really haven’t studied cannabis (long enough). People say, but it’s been around for centuries! If you think about it, every year we know more about alcohol. Ten, twenty years ago they were telling us it’s ok to have alcohol with dinner. Now, we’re finding those studies may have been inaccurate, the comparison groups were faulty, and in fact any dose of alcohol is involved in cancer.” The evidence base for cannabis as a safe substance is very thin, she concludes. Studying any illegal substance is difficult and classic studies of tobacco’s impact on cardiovascular disease, for example, involved following roughly 20,000 individuals for decades. “The idea we will know the cardiovascular effects of cannabis in five years is a hard proposition,” she concludes.

While following 4,000 individuals with coronary disease in a current study to determine cannabis’ possible negative effects, she admits, “We still haven’t answered the question. Cannabis is probably harmful; why wouldn’t it be? Why wouldn’t smoking be harmful to health? Smog, fires, and second hand tobacco smoke are harmful to human health. The fact that we don’t have studies doesn’t mean it’s not harmful. It means we just don’t have studies yet. Studies are forthcoming, people are working on this.”

Basing a hypothesis on ongoing studies of THC on the elderly, Keyhani says cannabis probably causes harm. (Tetrahydrocannabinol/THC is the psychoactive chemical compound in cannabis that produces the high sensation.) “We know from basic clinical safety trials that have been published, that THC is associated with dizziness, confusion, disorientation, tachycardia (rapid heart rate). I took (those findings) to form my hypothesis that this would have an effect on older adults, who are already taking medication for confusion and disorientation. We know from decades of research that psychoactive drugs cause falls and injury in the elderly. Why wouldn’t cannabis?”

A factor in people’s understanding—and incorrect thinking—about the effects of cannabis on lung function is reliance on reports that base their findings on outdated information. A paper published in JAMA had Keyhani emailing the writer to ask questions. “We know that low amounts of cannabis are not associated with deficits in lung function over 20 years. When you look at the paper, that is a correct finding, but what is “small amount of cannabis” use? In that JAMA paper, it’s people who have smoked one to two joints a month over 26 years. If you smoked one to two cigarettes a month over 26 years, would you get declines in pulmonary function? I don’t think so. You have to smoke a pack a day for 10 years, not two cigarettes a month. That’s an order of magnitude more. I’m not saying tobacco and cannabis are the same, but the dose matters. This paper had this low amount and said you’re not going to get declines in pulmonary function but I would say in response that if you smoked one to two cigarettes a month you wouldn’t get that decline either.”

The real question, she insists, is what happens if you smoke one to two joints a day? Maybe before cannabis was commercialized, nobody could actually smoke it that way. But cannabis has leapt from prohibition to legalization. “We’ve made cannabis into a small industry,” says Keyhani. “My question is, with the commercialization of cannabis and increasing potency with more THC, are people more likely to get addicted, are more people prone to smoke two to three joints a day? We can expect them to have bad lung detriments. People develop tolerance to THC; it’s a dose issue. Drink one to two glasses of wine a month, you might not have an adverse effect. But I believe inhalation of any particulate matter is harmful to human health. There’s no free pass with low exposure and we should never say smoking one to two joints a day is not harmful. We have to be careful in a time when good data isn’t there yet.”

Humphreys served during the Obama administration as senior policy advisor in the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy and worked with California Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom on the Blue Ribbon Commission on Marijuana Law and Policy. A conversation with Humphreys begins with the shifting perceptions about cannabis and how that impacts research.

“We’re romanticizing cannabis. Everyone wants to focus on how good it is, how it heals and cures. It has an industry now that’s marketed it as a cure for Covid in some states, and as a cure for cancer and diabetes. There’s advertising which makes people feel it’s better, safer for them. It makes it less likely for researchers to study the harms of cannabis. People in public health and academia are scared of being seen as dated, from the 1980’s, as in, “I’m not into cannabis, I’m into the war on drugs.” So there’s less looking into problems. But we’re definitely seeing them, with more people coming into emergency rooms and clinics for treatments.”

Humphreys says the FDA sent out warning letters telling states not to market cannabis as a cure for Covid. “We’ve done work showing it’s marketed telling people who are on buprenorphine, a really good treatment for heroin addiction, to stop taking it and replace it with cannabis. There’ve been warning letters from the FDA about that also.”

Substance addiction is among Humphreys’ special areas of expertise. He says forming patient-therapist relationships during the pandemic is challenging. “It’s not that big a deal if you’ve been in therapy for three months and now you’re going to go to the web. But to treat someone the first time over the web, it’s less intimate, you can’t notice the non-verbals, it’s less comfortable. It makes it harder and might take more sessions.” For certain patients, there’s one advantage to e-medicine. “You may not be willing or able to drive two hours to see a psychiatrist. This way, you can hop on the web and gain access directly.”

Younger patients are comfortable and trust online therapy more than do an older generation of patients who are forced online by the pandemic and didn’t grow up during the internet era. Humphreys says, “It’s a cohort effect and not due to Covid.” Digital delivery is improving, he suggests, with extended broadband and higher quality, more secure connections. Still, there is room for improvement. “There’s some research at Stanford showing Zooming is fatiguing. Clinicians are worn out. It takes more concentration to focus on Zoom. The distraction of screens, the time delays between what you see and hear.…maybe someday we’ll have perfectly synchronous timing but we’re not there yet.”

Asked about cannabis research funding during the Trump’s presidency, Humphreys says there was no diminishment in the amount of corporate-funded research into marketing, outreach, and how to make more potent products. Government-funded studies of medical applications for cannabis also remained stable. “During the Trump era there wasn’t attention on drug policy,” he says. “If they had paid attention, I think they would have screwed it up, but I don’t think they really did.”

Although Operation Warp Speed shifted attentional focus to Covid studies, it had a separate funding appropriation from Congress and did not drain money for ongoing cannabis research from the NIH and similar organizations. As more states legalize cannabis use, changes in one law are making a difference. Previously, you had to get cannabis for research from a particular farm in Mississippi. “That law is loosening up to allow more states or companies to operate cannabis farms. Trump definitely screwed that up because the Congress said that it was ok to grant licenses to others a long time ago, like five years ago. Jeff Sessions, the Attorney General, just sat on the applications; wouldn’t let them go forward. If not for Trump, it would have gone faster.”

Humphreys favors universal health care with expanded benefits for people with cannabis problems, which he equates to any other chronic health problem. “When you do that, you reduce disparities because lower income groups have lower rates of employment, work in jobs without health care benefits. You want any expansion to cover all use of cannabis, opioids and anything else. That’s important for equity.”

Considering current studies and the immediate future, Humphreys highlights a recent finding that legalizing cannabis did not lower opioid use. “Which will surprise your readers,” he says. “There were early much-valued studies suggesting that cannabis use would stop the opioid epidemic, maybe by substituting for pain medication? Then a study with more data and more years showed that it was exactly the other way around. The states with higher rates of cannabis legalization ended up with higher opioid overdose.”

Which leads to Humphreys’ primary point about FDA approved medications for opioid addiction. “You should never stop taking them and replace them with cannabis. That’s dangerous: there’s a chance of overdosing and dying. Even though there are programs saying you can replace heroin with cannabis, we have no evidence that works. You should be on FDA approved medication. That’s important in the middle of an opioid epidemic.”

Other studies examining cannabis’ impact on pain or anxiety are “not super encouraging,” he says. “What your budtender tells you is 800 miles ahead of what is actually known. There’s a lot more extravagant claims about medical cannabis than is evidence to support those claims. The buyer should beware.” About whether or not cannabis will reduce anxiety and related mental health symptoms, he says, “People who use cannabis will think it’s reducing their anxiety because they smoke it and feel better. It’s like if you’re anxious and have a shot of bourbon and feel more relaxed. I wouldn’t say that therefore bourbon is a good treatment for anxiety; it isn’t.”

Keyhani sums up the interview where it began; by encouraging patience as more data is drawn relating to today’s high-potency cannabis and there is time for longer studies with bigger cohorts. “With the advent of high-potency cannabis it would be interesting to look again at all these studies that are in the past. Ten or fifteen years ago they would say that cannabis was not very addictive. But with 100 percent concentration THC that is readily available in dispensaries, should we be rethinking the relationship? What is the relationship of cannabis and addiction and psychosis if you are dabbing, using cannabis every day? Have the rates in the U.S. increased? Are rates higher where high potency cannabis has become readily available?”

Because cannabis has been marketed as a safe analgesic, Keyhani wonders about its use by reproductive age women and how it might impact an infant. “If you’re using cannabis during pregnancy, how does that impact the children? As it’s being marketed to the public as a harmless substance, is use among high-risk groups increasing?”

Humphreys returns to his primary theme: cannabis is riding a positive cultural wave. “Cannabis is getting legalized on very big promises it will raise tax revenue, make society more equitable, and cure lots of diseases. I think we’re in a period of extremely low criticism of cannabis as an unvarnished good. (Eventually) people will realize the cannabis industry is run by very rich people, not by gentle hippies from the 60s. It’s guys in business suits and women with MBAs who want to maximize profit, increase addiction, just like tobacco.”

Although it is called medical cannabis, many experts emphasize that cannabis is one of the least regulated parts of the entire medical system. Humphrey agrees. “You can make claims about cannabis that would make you lose your physician’s license if you made them about any other medication. You can’t sue the budtender for medical malpractice because they are not medical. The cannabis budtender has prestige but not rigor and science from where that trust is derived. When you sell an edible or product, there are multiple studies showing that the packaging doesn’t even have to be correct. A cookie that says it has 5 mg has 25. Or one refers to one bite as a dose but another place it says five bites is a dose. You’re much less protected as a consumer than you might think.”

Asked to name best resources for people exploring the medical cannabis Wild West, Keyhani recommends reports from UCSF, the NIH, CDC, American Heart Association, American Academy of Neurology and the National Academy of Sciences. Humphreys directs consumers to Stanford University research and work being done by Dr. Ziva Cooper at UCLA’s Cannabis Research Initiative.

Protected by Patchstack

Protected by Patchstack